(Note: This is part one of a multi-part series. Today, I’ll be noting my concerns about mindfulness meditation and clarifying what mindfulness is and is not. Stay tuned for parts two through four, all of which work fine at stand-alone reads.)

I’ve been meditating for nearly thirty years and I’m a formally certified mindfulness meditation* teacher but recently, I started wondering if meditation has done me more harm than good. I’ve had many pandemic epiphanies around the problematic ways meditation has been ‘sold’ in the western world and the harmful ways it’s often taught. But my doubts have leveled up recently.

In the west, meditation is sold as a solution. Do you want to sleep/eat/focus better? Do you want to be more productive? Do you want to solve your pain problem? Research supports the benefits of meditation for all these issues and many more. And these selling points are a great hook to get people interested. But here’s the problem: a fundamental tenet of meditation is non-striving and release of attachment to outcome. It is literally impossible to do meditation if you are striving for a particular goal. The two actions are mutually exclusive.

Meditation is also taught in a rote manner that is not a fit for many, if not most Western lay folk. Most of us live in perpetual fight or flight. Many of us live there due to past or ongoing trauma. Some of us are just embedded in the stress of everyday life. The Buddha was not teaching meditation to people enmeshed in the physiological stress response inherent in modern society. Monks literally retreat to rarefied environments that are not at all easy but are also calm, constructed, and contained. Monasteries are in no way overstimulating.

Instructions like, ‘Just sit with whatever comes up, nonjudgmentally. It will pass, as all things do,” approach the bizarre in many cases. When we teach meditation to people whose nervous systems have been hijacked, telling them to just sit with their overwhelming feelings is the equivalent of insisting that a person living with domestic violence must stay put. In both cases, the obvious choice is to get the f*%$ out of there.

Mind you, just passively being with experience is not what meditation is. At least, it’s not all that meditation is. But it is the way it’s taught for the most part, and it is the reason why most people feel they ‘fail’ at it. The failure is not yours, dear reader. It’s the fault of the legions of Western teachers who lack flexibility of approach, knowledge of pedagogy, and understanding of cultural and personal context. And let me say here: there are two arms in the embrace of meditation: one that requires acceptance of what is and the other that encourages action toward change. I refer to these as ‘being with’ and ‘working with.’**

All these concerns are the backdrop to my current angst. Which is…

After decades of mindfulness meditation practice – countless hours of gently bringing my mind back to the present moment whenever I notice that it’s wandered – I am an absolute pro. This is a good thing, right? I mean, it’s the stated objective of mindfulness. I’m constantly directing myself to be in the moment.

It turns out that this may not be such a good thing after all. Recent ‘aha’ moment: I am literally doing this constantly in the background. Bringing my mind back from wherever it has wandered. Not just when I meditate. Always.

What I realized is this: Rather than freeing myself up to be present, I am perpetually controlling my experience. And worse, to a large degree, this is occurring outside my awareness. I don’t even realize when I’m doing this. This is the exact opposite of the intention of mindfulness, where the exercise is meant to release control. We are meant to acknowledge that we actually have precious little control over anything and to greet that awareness with gentle acceptance.

OMG! Where did I go wrong???

More questions arise: What am I missing in life when I perpetually drag my mind back to the present moment? How have I quashed my creativity and spontaneity, qualities that require freedom to mentally roam?

This is the issue I’ll be parsing in this series of articles. Not just what went wrong for me, but what is ‘mindfulness’ really? When does it serve us? When does it constrain us? How to decide when to use a given tool or put it aside?

I’m taking you with me on this journey – back to the basics and then beyond. My goal: to deliver answers to some of these questions and also to help you generate questions of your own about the utility of these practices and what really fits for you.

Part 1: A deep dive into the meaning of mindfulness – both what it is and what it is not.

Part 2: An exploration of three different approaches to mindfulness, two of which are much more accessible and – dare I say, enjoyable – than meditation.

Part 3: An exploration of the problems that mindfulness meditation attempts to address and the problems it creates along the way.

Part 4: A how-to of what I call ‘Mindful Moments’ – a few mindfulness exercises that will require little extra time on your part but will deliver meaningful results.

Take a deep breath, and let’s dive in.

What is Mindfulness?

“And all my instincts they return. And the grand facade, so soon will burn. Without a noise, without my pride, I reach out from the inside.”

– Peter Gabriel

Not long ago, few people had heard the term ‘mindfulness’ and, if they did, it carried with it a hippie-dippy connotation, at best. Starting in the 1980s, John Kabat-Zinn began to drive ‘mindfulness’ into the mainstream. Developing medical-center-based clinical research programs, he studied the effects of mindfulness meditation and caught the attention of the media, landing on the cover of Time magazine and appearing on the news magazine 60 Minutes multiple times. He became the father of western meditation and a media darling – spreading the good word about meditation far and near.

At this point, ‘mindfulness’ is the poppiest of cultural buzzwords. But I’m not convinced that most people really understand what it is or what the term means.

In common parlance, mindfulness is simply knowing what’s going on. But what does that mean exactly? Knowing in what way?

Formal definitions of mindfulness abound and range from extremely dry and academic – where everything has to be defined in quantifiable, replicable terms – to simple and pithy catch-phrases. My favorite definition set me on my meditation path. It’s the title of controversial teacher and sage, Ram Dass’ first book, Be Here Now – and it’s as much a definition as a command. You can hear the urgency in the plea. Be. Here. Now. How often are we fully present in any moment? How much of life do we miss in our absence from this moment, right now?

Of course, it’s not quite that simple. Being here now is far from easy to do on command and the simple statement belies the complexity of showing up on a regular basis. It’s one of those things that’s far simpler to say than to do.

Let’s look at the key components of mindfulness and build a definition that, while far less catchy, fleshes out the process.

- Mindfulness is the capacity to pay attention, moment to moment, on purpose. We’re talking about focused attention on whatever is happening in this moment right now … And in this moment, right now … And in this moment, right now. In other words, this is not simply about being present. It’s about staying present. Or learning to stay present. Or practicing the act of being present, over and over.

- This paying attention is carried out without judgment. This is challenging. We are judging machines – constantly scanning the environment and assessing what we find there for safety. We are built this way, and we carry this trait for good reason. It’s a survival mechanism. So, if a thought, feeling, or sensation comes up, your first job is to notice it, your second job is to accept it without judgment, and your third job is to refrain from judging yourself if you find yourself judging. See what I mean about the complexity of this activity?

- Attending to whatever is present moment-to-moment also includes the practice of tuning in to our sensory experiences. It’s one thing to be aware that you’re drinking a cup of tea. It’s another thing to be fully attuned to the warmth on your hand and tongue, the aroma, the nuances of taste, the fullness of your belly. In the first case, you may be absent – simultaneously texting and listening to music perhaps – fully present for none of those activities. In the second case, you’re fully engaged in the experience, which then becomes expansive and enriched.

So, mindfulness isn’t just about knowing that you’re breathing, that you’re hearing something, seeing something, or having a particular thought or feeling. It’s about doing so in a specific way — with balance and calm and without judgment.

What Mindfulness is Not

In some ways, it’s easiest to understand what mindfulness is by understanding what it’s not. It is not distraction, which is our typical way of living. We tend to function within what I refer to as the Three Distractions.

- Busy minds

Humans seem to be constantly reviewing the past (often in the form of regrets) or anticipating the future (often in a worried or anxious way). Most of us have a ticker-tape running in our heads – a continual stream of commentary and criticism either toward ourselves or others. Just like a stock market ticker tape, the content tends to cause a lot of pain – particularly on a day when you (or the market) are down. Our mental ticker tape is constantly running. - Overcommitted lives

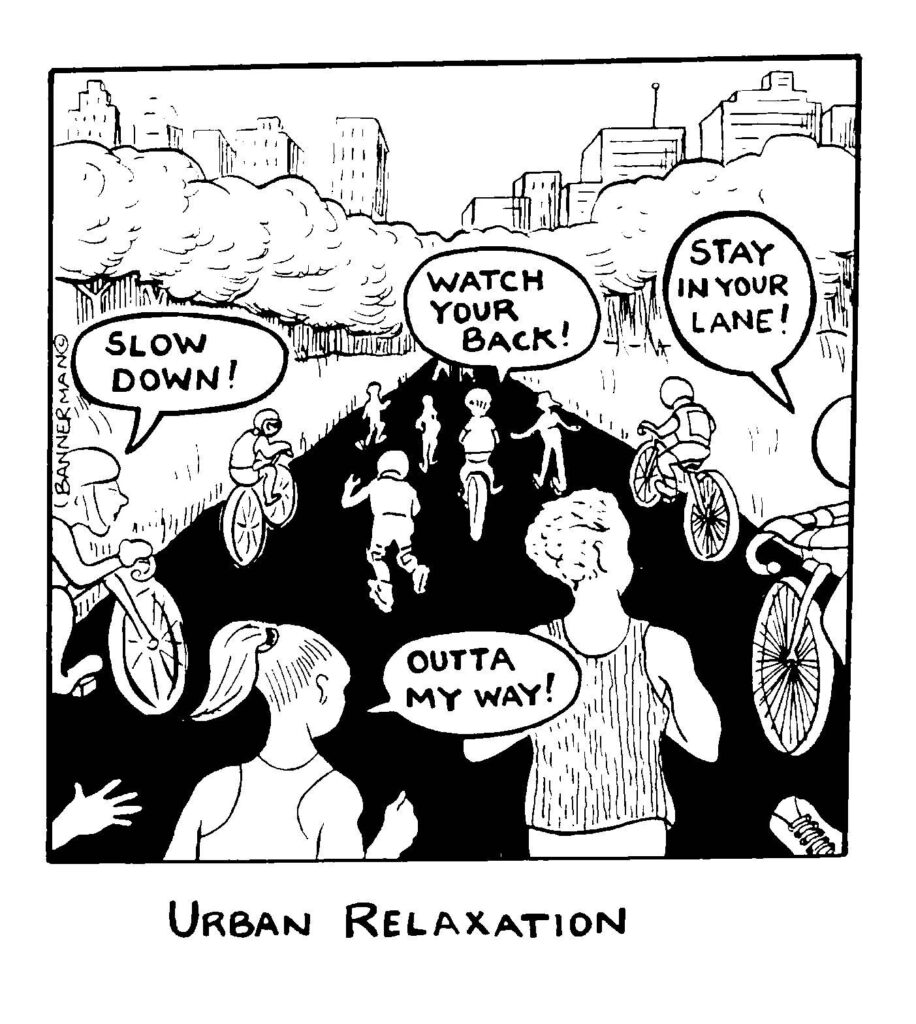

Busyness is the American way of life. It’s a style that’s spreading across the continents, with all the negative repercussions that our fast-food fascination has had across cultures. Sometimes we’re multitasking – despite knowing that research condemns this activity as an absolute efficiency fail. Other times, we’re simply stuffing our lives to the brim in the name of productivity. Overflowing lives often mean that we’re not there for the people or activities that matter to us. We don’t take the time to turn inward and ask, “what is most important to me now?” - Culturally-induced ADHD

We live in an attention-less world.

Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common childhood disorders and can continue through adolescence and into adulthood. Symptoms include difficulty staying focused, paying attention, and controlling behavior, and often include hyperactivity (over-activity). Rates of ADHD diagnoses have climbed dramatically in the past decade and while the causes are hotly debated, the reality is that Americans are less and less able to attend to the present moment.

Worse, there’s a type of inattention that I refer to as ‘Culturally-induced ADHD’ in which we are trained into a perpetually distracted state by our devices & the demands of our communities. None of us can seem to pay attention anymore, and we’ve noticed. And we’re worried.

In sum, the mindfulness revolution has gained its momentum partly because we are desperate to find a way to stay connected to the here and now. We understand how much we’re missing in our absence, but are powerless to fight the sociocultural forces that breed our distraction. The reality is that we are rarely here now…if ever.

You Are Here

As we end the first part of this series, let’s locate ourselves on the journey.

So far, we’ve discussed:

- My concerns about mindfulness – particularly how it’s presented in the West: It is most often solutions-oriented and trauma-insensitive, disregarding the cultural and personal context of our daily lives.

- My personal concerns about mindfulness. Practicing (over-practicing?) mindfulness meditation seems to have programmed me rather than freed me. I am willy-nilly bringing my mind back to ‘the present moment’ regardless of what my mind is doing or the value of its activity. And I’m doing this unconsciously. Less awareness rather than more.

- What mindfulness is: the capacity to pay attention, and keep paying attention, moment to moment, on purpose, without judgment, including the full breadth of sensory and emotional experience.

- What mindfulness is not: our normal mode of living which tends to be distracted, frenetic, and crammed to overflowing.

Here are a couple of questions for you to consider. I’d love to hear your thoughts if you feel inspired to share.

- How do my concerns about meditation resonate with you? Do they help you understand why meditation is difficult or uninteresting to you?

- It’s easy to define meditation in one brief sentence. Did this deeper dive – the breakdown of component parts – spark any new realizations, questions, or concerns for you?

In Part 2, we’ll dive into the three modes of mindfulness. They all have advantages, but the barrier to entry with non-meditation approaches is far lower, providing options for people who don’t have the time or patience to capture some of the same results.

* In this article, all discussion of ‘meditation’ refers to mindfulness meditation specifically.

** ‘Being with’ and ‘working with’ are terms popularized by the wonderful psychologist/philosopher Rick Hanson.

+ Cartoon by Isabella Bannerman (https://www.isabellabannerman.com/)

0 Comments